20 Years of Impact

What we've accomplished together with our partners (2004 – 2023)

Report Contents

Origin

The Sierra Nevada Conservancy was formed in 2004 responding to a growing consensus that the Sierra Nevada was in peril.

Project Impacts

Our grants support work in three critical categories: wildfire and climate resilience, land conservation and stewardship, and outdoor access.

Policy Highlights

We connect local knowledge and expertise from the Sierra-Cascade with natural resource policymakers.

Investing in Partners

Meeting California's natural resource conservation goals requires a robust network of local stewards in the Sierra-Cascade.

Dramatic Changes

The legacy of past land-use decisions and climate change have led to stark changes for many Sierra-Cascade landscapes and communities.

Looking Ahead

The Sierra-Cascade is at an inflection point. With investment and dedication, the next 20 years can be a story of regeneration, recovery, and renewal.

SNC Origin

“With this bill, we issue our declaration that our children and grandchildren will see and enjoy the same Sierra Nevada that we value so much today....The Conservancy service area is a gift to the people of California.”

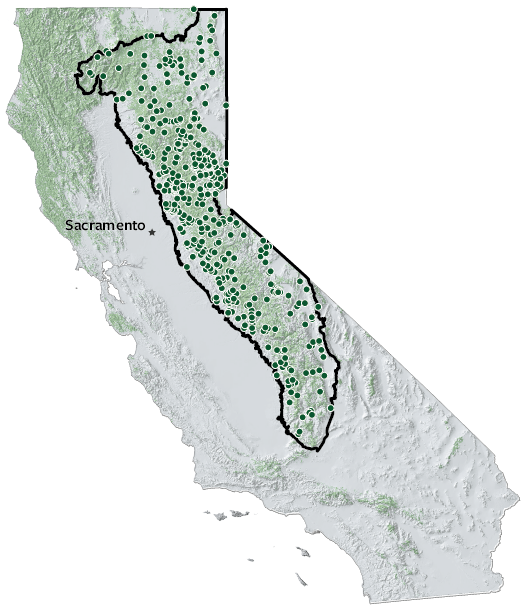

From the Mojave Desert in the south to the heights of Mt. Whitney and up north to Mt. Shasta and the Oregon border, the Sierra-Cascade is a critical region to all Californians. While it was known that an increase in human activities, such as logging, mining, and urban development, over the past 100-plus years had put the Sierra in peril, the extent of the mounting damage was unknown. A main reason for this was the simple fact there was no private or governmental agency focusing its attention on this vast, but vital area—not until the passing of the historic legislation that created the Sierra Nevada Conservancy in 2004.

When Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed the Laird-Leslie Sierra Nevada Conservancy Act into law, which officially created the Conservancy, he announced: “AB 2600 is common sense legislation to preserve and protect our environment and allow everyone to enjoy our Sierra Nevada Mountains for years to come.” Since that historic time 20 years ago, the Sierra Nevada Conservancy has been devoted to environmental protection, resource conservation, recreational opportunities, and economic growth to ensure generations to come continue to enjoy and benefit from one of the greatest natural gifts bestowed on humankind—California’s incredible Sierra-Cascade.

Impacts on the Ground

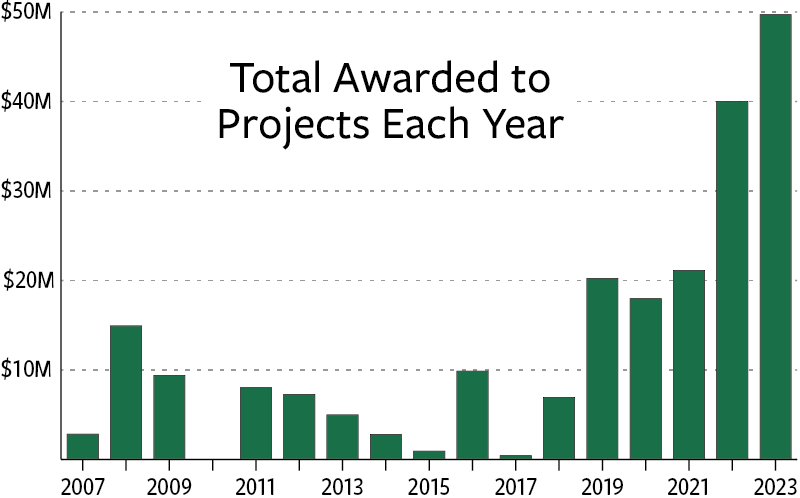

We've awarded $218 million to 589 projects throughout the Sierra-Cascade region, promoting wildfire and climate resilience, conserving natural and working lands, and improving outdoor access.

Wildfire & Climate Resilience

Restoring health to our forests and protecting communities throughout the Sierra-Cascade is of critical importance, especially with more people moving to the region, a changing climate, and a rise in destructive wildfires. At the heart of our work is investing in the planning and implementation of projects that build essential forest resilience and greatly reduce the risk of damaging wildfires.

- 155,000 acres treated

- 850,000 acres under planning

- 18 projects protected communities & landscapes from megafires

Types of projects:

- 234 fuels reduction

- 111 community protection

- 87 meadow/stream restoration

- 30 fuel breaks

- 27 biomass utilization

- 17 water infrastructure

- 16 reforestation

Project Highlight:

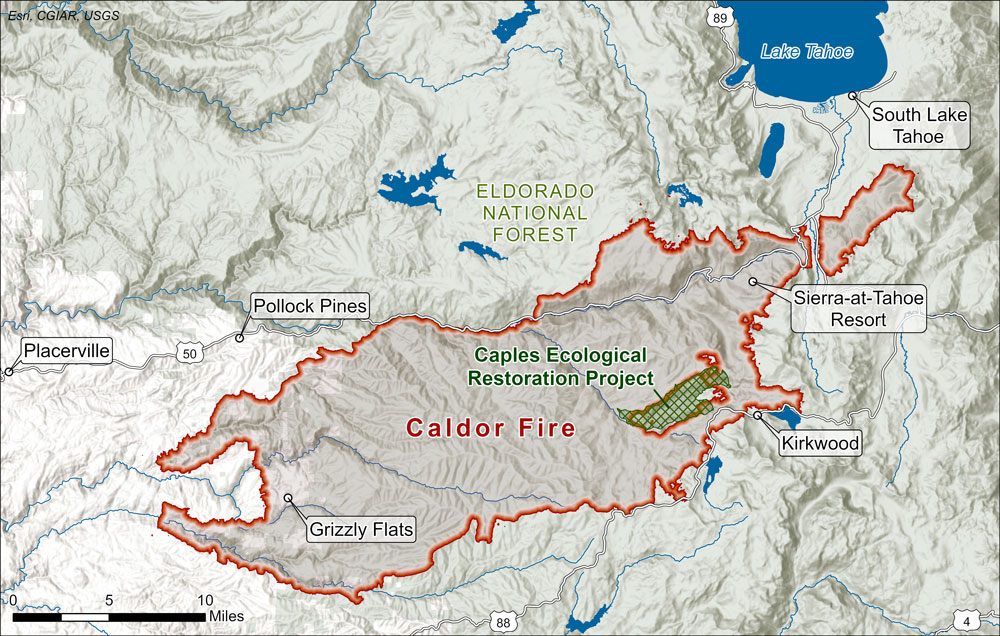

Caples Creek Watershed Restoration

We funded the planning and implementation of a 4,400 acre prescribed fire project by the El Dorado Irrigation District in the Caples Creek watershed of the Eldorado National Forest. Its goal was to restore resilience to the primary headwaters of the El Dorado Irrigation District’s water supply and protect it from an event like the 2014 King Fire.

After a week of prescribed burning operations in October 2019, strong winds forced the need for additional wildfire-suppression resources to control fire behavior. The Eldorado National Forest quickly contained the newly declared Caples Fire, and the combined prescribed fire and wildfire remained almost entirely within intended boundaries and created burn effects consistent with desired outcomes. Combined costs remained far below mechanical treatment options.

Two years later, the damaging 220,000-acre Caldor Fire came roaring up to the Caples Creek watershed. Not only was the treated area resilient (the fire barely burned past its edges), but it helped to slow down the Caldor Fire and change its course, aiding firefighters' forest- and community-protection efforts. Learn more

Project Highlight:

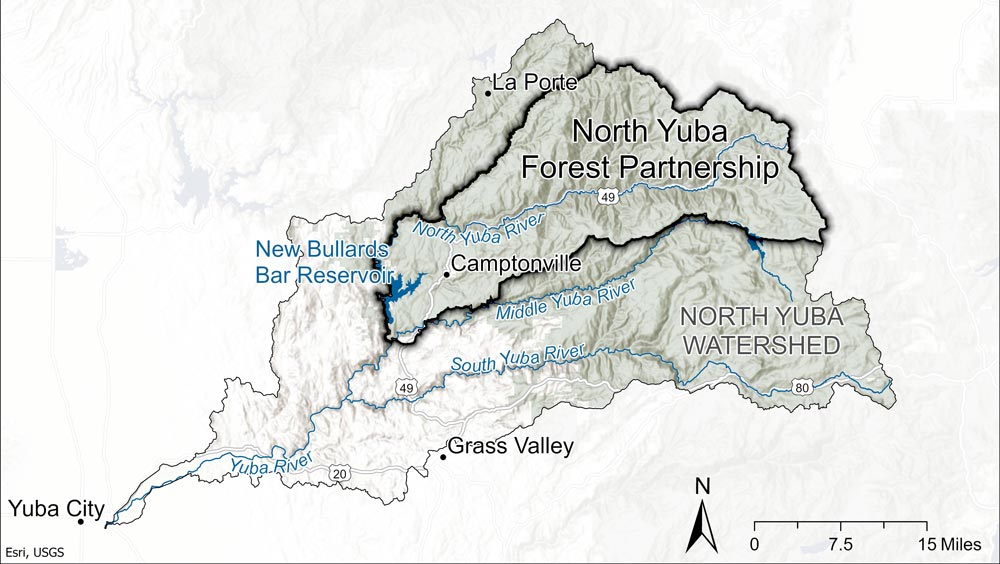

North Yuba Forest Partnership

We provided two early grants that would help inspire and organize the North Yuba Forest Partnership. The first was $500,000 to Sierra County to reduce fuels along the North Yuba River above the community of Bassets, and the second was $250,000 to the South Yuba River Citizen’s League to facilitate landscape-level planning efforts. The funding helped bring together a diverse and representative coalition of governmental and non-profit entities to form the North Yuba Forest Partnership and create a plan for the watershed.

In 2022, the Tahoe National Forest completed environmental analysis and permitting for this plan to restore wildfire and climate resilience across the 275,000-acre North Yuba watershed and was selected as one of the US Forest Service’s 21 Wildfire Crisis Strategy Priority Landscapes that same year. It has subsequently received approximately $160 million in federal funding, jumpstarting the Partnership’s work to restore resilience to the North Yuba River watershed from Yuba Pass to Bullards Bar Reservoir. Learn more

Project Highlight:

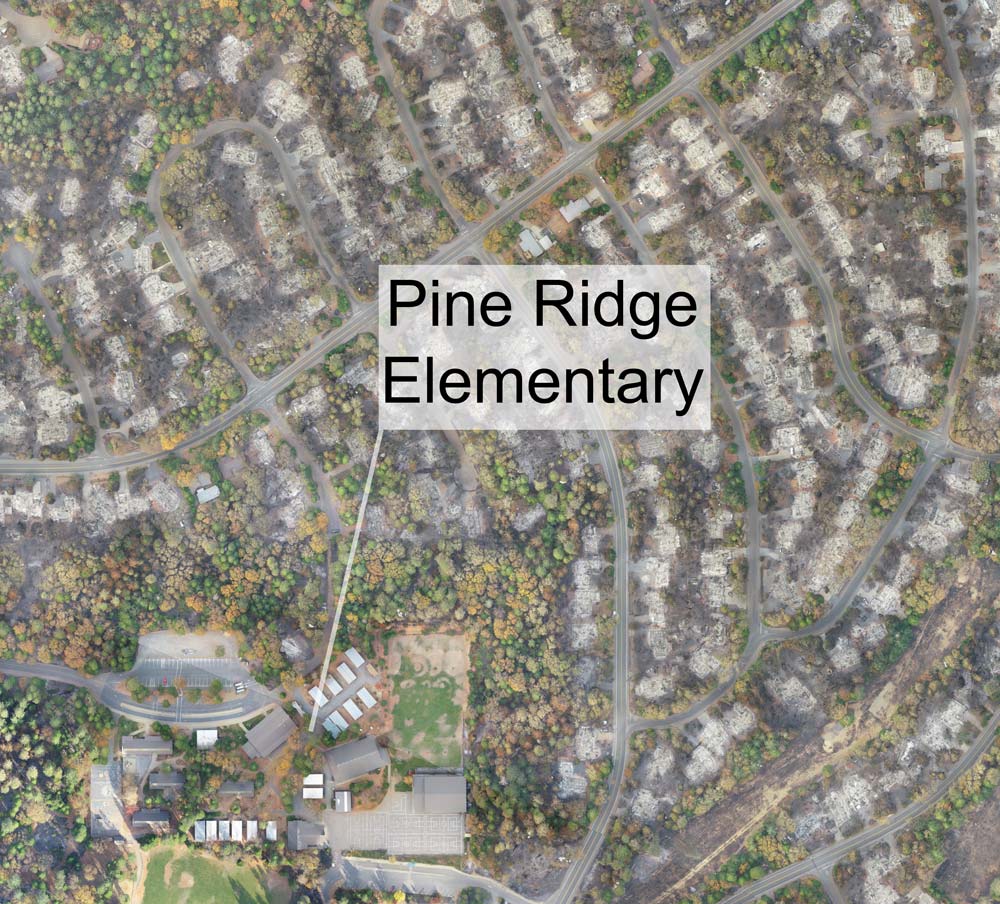

Little Butte Creek Projects

The 2018 Camp Fire took 85 lives and left behind a mostly scorched landscape of dead trees and burned homes. Amidst the destruction remained pockets of green trees, unburned neighborhoods, and Pine Ridge School. These pockets of protection were created by the synergistic efforts of the Butte County Fire Safe Council, which thinned forests in these areas prior to the Camp Fire using $1 million in SNC funding, and firefighters working during the blaze who were able to minimize damage in these areas due to moderated fire behavior.

According to David Hawks, CAL FIRE Unit & County Fire Chief, Butte County, the forest-health work funded was critical in helping to stop the fire from advancing into one popular Magalia neighborhood. “When the fire did cross the drainage, it wasn’t so intense and firefighters were able to pick it up and get on it, which has a lot to do with why that Fir Haven community, as a whole, was spared,” he said.

“We’ve lost three public schools (to recent fires)…It’s really devastating when your community doesn’t have a school,” noted Butte County Fire Safe Council Executive Advisor Calli-Jane West, talking about Pine Ridge School, the local elementary school that survived the Camp Fire. Hawks added, “That school was only spared because of the fuel-reduction work that was completed a few months before the fire.” Learn more

More Wildfire & Climate Resilience Highlights

Land Conservation & Stewardship

In our desire to continue to enjoy the great outdoors and preserve lands of significant natural and cultural value, permanently protecting and managing these vital areas throughout the Sierra-Cascade remains a top priority. Since our founding, we have funded planning and implementation projects that align with the key strategic goal of preserving and protecting working and non-working lands.

- 84,000 acres (70% working lands, 30% non-working lands) conserved

- 1,400 acres returned to tribes

Project Highlight:

Cinnamon Ranch Conservation Easement

In 2011, we contributed $735,000 to help purchase an agricultural conservation easement on the 602-acre Cinnamon Ranch in the Owens Valley, incorporating it into the Eastern Sierra Land Trust's working farms and ranches program. A historic alfalfa hay ranch, the easement encouraged continued agriculture productivity by limiting development in prime farmland area and also protected wildlife habitat for a variety of species, including bighorn sheep, mountain lions, and waterfowl.

The conservation easement has had significant, positive ripple effects in the small community of Bishop, CA. First, it allowed the family to reinvest in the ranch by hiring additional ranch hands and modernizing farming and grazing practices to conserve water and protect water quality. Next, the family started two new businesses, one that shared these modern, waterwise, agriculture practices with other farmers and ranchers in the valley and the other is a downtown bishop bookstore and ice cream shop that, at its peak, employed 7 additional residents. Learn more

Project Highlight:

Ackerson Meadows Acquisition

In 2011, American Rivers learned that the owners of a 400-acre meadow on the edge of Yosemite National Park, long sought by developers and Yosemite National Park alike, were interested in conserving their land. Under a tight deadline, they turned to the Sierra Nevada Conservancy for a relatively small $70,000 grant to complete the land appraisal and environmental assessment necessary for a conservation acquisition. The due diligence laid the foundation for a conservation agreement and joint fundraising efforts by the Trust for Public Land, Yosemite Conservancy, the National Park Trust, and several other state and federal funders to purchase the property. It was then transferred to Yosemite National Park in 2016, making it the park’s largest expansion in 70 years.

Home to many special status, threatened, and endangered species, the meadow holds incredible importance. That is one reason why in 2023, American Rivers, working in partnership with Yosemite National Park, broke ground on an ambitious meadow-restoration project to restore ecological and hydrological functionality. Part of our original grant funded a comprehensive habitat assessment, which became the starting point for this effort—Yosemite National Park’s largest wetland restoration undertaking ever and one of the largest in the Sierra. Learn more

Project Highlight:

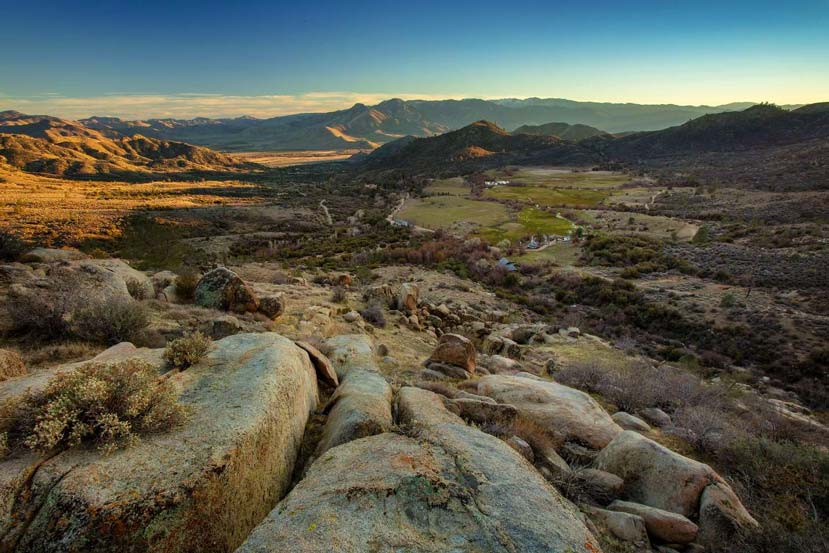

Kolo Kam’ap (Fay Creek Ranch) Acquisition

The Tübatulabal Tribe calls an unusually green valley where the southern Sierra meets the Mojave Kolo Kam’ap (“duck place”) for its importance as a wetland stop for migratory birds. Thanks to the work of the Western Rivers Conservancy and funding from us and the Wildlife Conservation Board, 2,274 acres of this culturally significant land were purchased for preservation—and more than half of these acres transferred to the Tübatulabal Tribe for long-term stewardship as a working ranch. It was the first time culturally significant land was returned to the tribe.

Fay Creek Ranch is one of significant cultural value, but one of vital ecological value, as well. With an additional 800 acres being transferred to the Kern River Valley Heritage Foundation, these protected lands will expand an important wildlife migration corridor that links low-lying desert habitats with the mountainous Sierra, and preserve the ability of natural systems to adapt to a warming climate. Learn more

Outdoor Access

While the Sierra-Cascade provides much-needed necessities of life in clean air and water, it also offers a plethora of popular, recreational lifestyle opportunities, as well. Our grants not only support projects that enhance and develop sustainable recreation throughout the region, but also increase access to public lands, including for adults and youths in underserved communities.

- 120 miles of trail constructed

- 740 miles of trail planned

- 18 properties opened to recreation

- 15 sites improved for public use

Project Highlight:

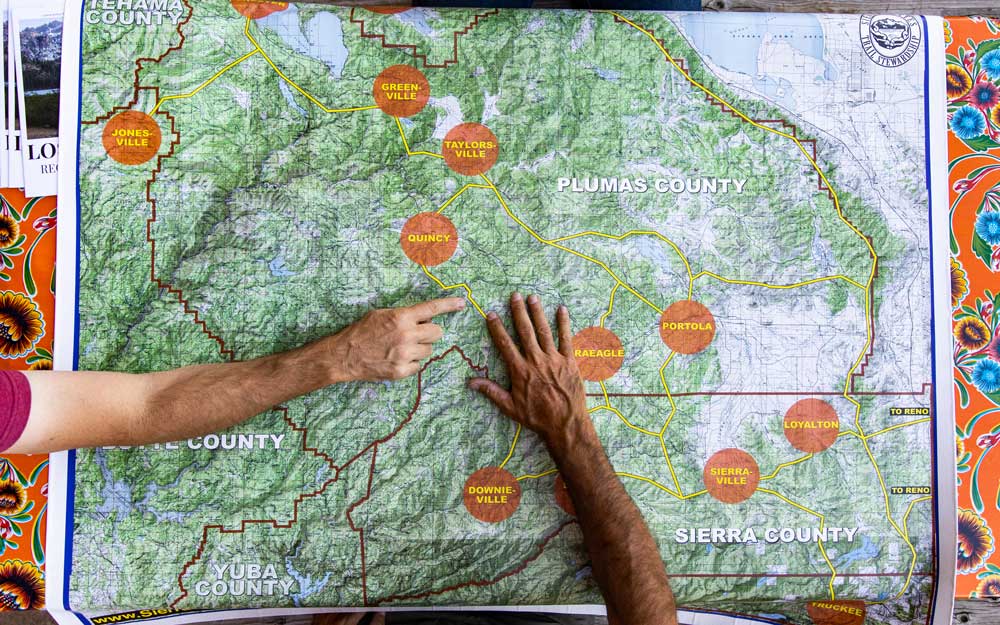

Connected Communities Project

The Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship’s Connected Communities Project aims to revitalize rural communities in California’s Lost Sierra (Sierra, Plumas, and western Lassen counties) using trails as its tool. In 2020, we helped to launch the project with a $360,000 grant, which funded the creation of a 581-mile Connected Communities Trails Master Plan that envisions 15 exceptional local trail networks with downtown trailheads in communities, including Susanville, Greenville, Quincy and Portola.

Utilizing funding from us and other sources, 30 miles of new trail envisioned by the plan have already been built, with another 10 under construction and 27 more “shovel ready” waiting for funding. An additional 73 miles are undergoing environmental review. The Connected Communities project is well on its way to establishing an iconic Lost Sierra Route that will create a new way for visitors to experience these special landscapes and support the economic resilience and recovery of a region hard hit by recent megafires. Learn more

Project Highlight:

Grizzly Creek Ranch Acquisition

Since 2010, kids from California and northern Nevada, including youths from low-income families, have been enjoying the outdoor, educational programs provided by Sierra Nevada Journeys at Grizzly Creek Ranch. With the help of a $1 million grant, Sierra Nevada Journeys was able to purchase the 462-acre Grizzly Creek Ranch in Plumas County, securing a permanent home for the experiential outdoor education programs and preserving important natural resources in the Feather River watershed.

Nearly 55 percent of the more than 200,000 kids who have attended Grizzly Creek Ranch have been from families with financial barriers, and 70 percent are students of color. The nonprofit organization is able to do this by offering scholarships to families in need, so the purchase will ensure accessibility to outdoor programs for underserved students across the region. The acquisition also means the property will remain undeveloped, protecting scenic Sierra Valley land, including a 50-acre riparian area, pond, intermittent stream, alpine meadows, and Big Grizzly Creek. Learn more

Project Highlight:

Wakamatsu Farm Acquisition

In 2009, we contributed $1 million to the American River Conservancy’s acquisition of the Gold Hill Ranch and Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony. The 272-acre purchase preserves two historic sites of national and international value—the first Japanese settlement in North America (est. 1869) and the gravesite of the first Japanese immigrant to pass away on American soil. Near the community of Coloma in El Dorado County, the site is also an active working organic farm providing a place to experience natural resources, sustainable agriculture, and cultural history.

The purchase also protects the scenic, open landscape, which contains a small lake, six springs, and unique low-elevation wet meadow areas that feed into two major tributary streams to the American River. This preservation will safeguard and improve critical water quality and supply in the American River watershed. Learn more

Connecting Local Knowledge with State Policy

Our investments in the Sierra-Cascade align with growing state recognition of our importance to California’s water, wildfire, and climate goals.

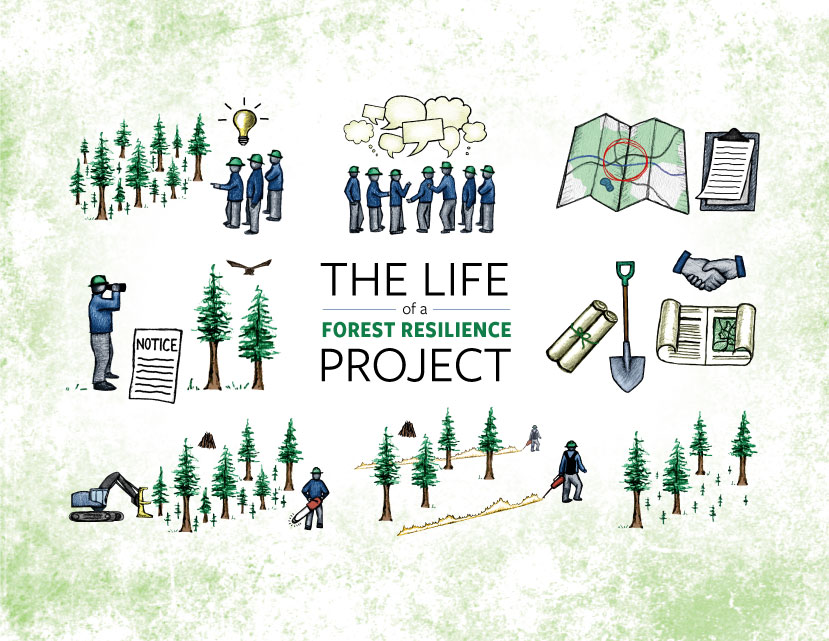

Watershed Improvement Program

We launched our Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program (WIP) in 2015 to draw attention to the need for increased investment and policy changes to support large-scale, holistic efforts to restore resilience to the forested landscapes and communities within the Sierra-Cascade. As the WIP developed, it sought to support partners for every stage of the life of a forest-resilience project, from convening partnerships to identifying landscape needs through project implementation and completion.

The success of this approach led to the codification of the WIP by the California Legislature in 2018 and its elevation as a model for addressing restoration at a landscape scale in state plans and strategies. In turn, this inspired other vital California programs, such as the Department of Conservation's Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program.

Since the WIP was launched in 2015, we have held an annual WIP Summit on new and emerging issues in the Sierra-Cascade. Our strong relationships in the region allow us to bring the real-time, real-world, on-the-ground experiences of our planning and implementation partners to relevant Sacramento policy conversations.

“The Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program is modeled after the Sierra Nevada Conservancy’s Watershed Improvement Program. The Watershed Improvement Program serves as an example of a coordinated, integrated, collaborative initiative to restore the health of large watersheds.”

Informing State Priorities

As a department of the California Natural Resources Agency, we have the opportunity to engage early in the development of state legislative strategies and executive action plans. This allows us to share insights about statewide proposals that may impact the Sierra-Cascade and highlight where the region is vital to statewide natural resource strategies.

In 2014, we published our first The State of the Sierra Nevada's Forests report in response to growing concerns around forest conditions due to recent wildfires. That report estimated the 2013 Rim Fire created as much greenhouse gas emissions as adding 2.3 million cars to the road for one year. Refined by the U.S. Forest Service and NASA researchers, this estimate helped lay the groundwork for California’s Forest Carbon Plan and the inclusion of forest-health projects in the state’s greenhouse gas reduction efforts.

In 2018, California dedicated $200 million per year from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction fund for forest carbon projects. Since 2019, counties in the Sierra-Cascade region have received over $422 million of that funding, which has significantly increased the pace and scale of partners’ forest-restoration work.

Investing in our Partners

We invest in our partners like our mission depends on it. That’s because it does. Unlocking the local knowledge and expertise of Sierra-Cascade organizations are essential to achieving California’s natural resource conservation goals.

Technical Assistance

We help partners design projects and access funding:

- 369 funding consultations

- 65 grantwriting workshops (with 800+ participants)

- 35+ collaboratives we participate in

Grants by Partner Type

Our grants support a variety of stewards in the Sierra-Cascade:

- 194conservation nonprofits

- 111land trusts

- 77resource conservation districts

- 65fire safe councils

- 52state & federal land managers

- 46city & county governments

- 18water agencies

- 12colleges & universities

- 9tribes & tribal nonprofits

Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program

We are a Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program (RFFCP) Regional Block Grantee and have distributed $8.8 million back into the Sierra-Cascade region to build the capacity of local partners to plan and design projects. To date, these investments have leveraged an additional $121.7 million in state, federal, and private funding.

Regional Events Supported

We've supported 116 events coordinated by Sierra-Cascade organizations across our service area. These range from river cleanups and educational events for youth interested in careers in conservation to scientific conferences and other knowledge-sharing activities. Events like these deepen the expertise of our local stewardship partners and strengthen civic life in the Sierra-Cascade.

One of these events, the Great Sierra River Cleanup, has hosted 32,926 volunteers and removed 1,684,355 pounds of trash from the waterways of the Sierra-Cascade over its 14-year history, helping to protect key sources of California’s water supply. The Great Sierra River Cleanup, originally inspired by the South Yuba River Citizens League’s Great Yuba River Cleanup, is hosted in conjunction with California Coastal Cleanup Day—one of the largest volunteer events in the state. The event is now coordinated by the Sierra Nevada Alliance.

Dramatic Changes in the Sierra-Cascade

Many modern fires—megafires—are burning larger and hotter than historical fires. They leave behind huge landscapes of blackened trees and vegetation, like the 2020 Creek Fire (pictured).

All Californians depend on the Sierra-Cascade region for healthy and resilient ecosystems that provide clean water, unpolluted air, healthy vegetation and soils, as well as revenue associated with forest products, agriculture and ranching, and recreation on its vast public lands. Supporting the health and resilience of these ecosystems depends upon resource experts, land managers, Indigenous communities, and other caretakers to steward forests, waters, meadows, grasslands, and sagebrush steppe.

These values, unfortunately, remain at high risk.

The region continues to reckon with a legacy of fire suppression, removal of native peoples from their homelands, and destructive and antiquated mining, timber and grazing practices – all of which have increased the vulnerability of our natural and working lands to drought, pathogens, fire, floods, and other stressors. Historical land-use policies have fragmented habitat and limited access to public lands. Simultaneously, widespread demographic and economic shifts are displacing and marginalizing many of the people who have long lived and worked in the Sierra-Cascade.

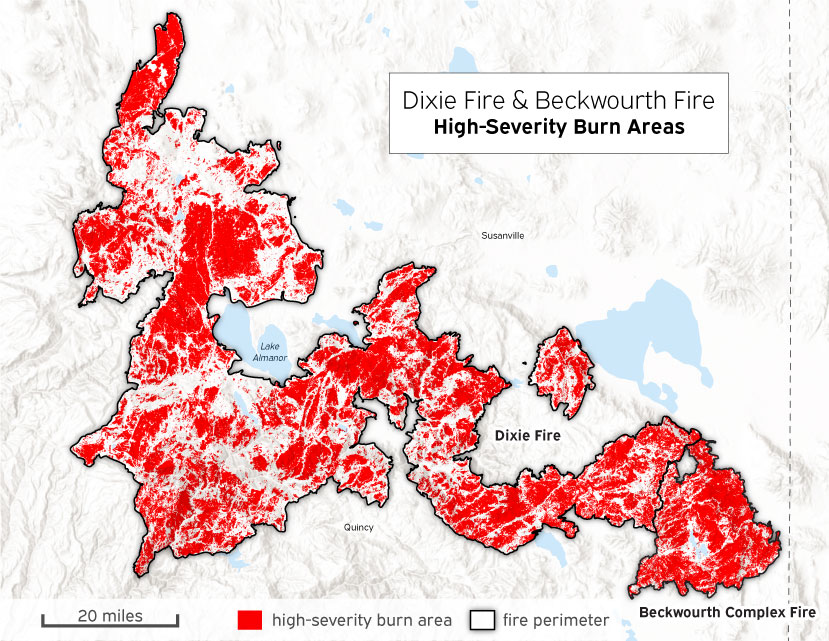

The Age of Climate Change and Megafires

Around the turn of the 21st century, scientists and land managers became increasingly concerned about the significant increase in the number of acres within a forest fire burning at high severity, from an average of 20 percent in the mid-1980s to over 30 percent by 2010. This concern exploded into the public consciousness in 2013 when the Rim Fire burned 257,000 acres, nearly 40 percent at high severity, in and around Yosemite National Park. At the time, it was the largest fire in recorded history of the Sierra-Cascade and prompted publication of our 2014 report The State of the Sierra Nevada’s Forests.

The following year, the King Fire burned nearly 100,000 acres at 50 percent high severity. The 2017 Railroad Fire was the first to burn so hot as to wipe out entire stands of giant sequoia. Then the 2018 Camp Fire burned over 153,000 acres, killing 85 people and destroying more than 18,000, structures including 95 percent of the towns of Paradise and Concow. The age of Sierra Nevada megafires had arrived.

Over a similar time period, much of the southern Sierra was gripped by an unprecedented multi-year tree mortality event. Unnaturally dense stands of trees proved no match for the stress of competing for scarce water during a multi-year drought, leaving entire landscapes vulnerable to pine beetle outbreaks. As reported in our 2017 update to The State of the Sierra Nevada Forests, 83 million trees died in the Sierra Nevada from overgrown forests, bark beetles, and drought between 2014 and 2016. Previously green hillsides turned brown with dead pine trees.

Compounding Crises

In 2020, somehow, it got worse. An August lightning storm ignited fires across the state, leading to a record-breaking 2020 fire season in the Sierra-Cascade. More than 3,500 structures were lost in the North Complex Fire, the Creek Fire blackened vast landscapes, and thousands of mature giant sequoia were killed in the SQF Complex Fire.

The season doubled the previous record for acres burned (set in 2018) and the amount, and arrangement, of high-severity fire in 2020 was unlike anything the region had experienced in the past. Scientific literature describing historical fire regimes refers to high-severity burn "patches", relatively small areas within a mosaic of fire effects where nearly all vegetation is killed. In contrast, these megafires created large high-severity burn landscapes that contained small patches of other, less severe, fire effects.

That was followed by another record-setting fire year in 2021, when more than 1.5 million acres burned in the Sierra-Cascade. The Dixie Fire became the largest single (non-complex) fire in state history, burning 983,309 acres across five counties, which included a single, 290,000-acre, high-severity patch and the destruction of the historic town of Greenville. It was one of two fires, the other being the Caldor Fire that consumed the town of Grizzly Flats and burned more than 220,000 acres, to burn up and over the crest of the Sierra Nevada—the first time in recorded history. The Windy and KNP Complex fires struck in the southern Sierra Nevada, killing thousands more giant sequoia.

These fires burned during, and were influenced by, another extended, extreme drought. From 2020 to 2022, California experienced the driest three-year period on record, leaving reservoirs depleted and the Sierra-Cascade almost devoid of snowpack. Although the dramatic tree mortality event of 2012-2016 has not been replicated, rates of mortality continue to rise: aerial detection surveys show generally elevated non-wildfire mortality, with moderate to very severe mortality in the central and northern Sierra Nevada.

Elevated tree mortality is concerning in and of itself, but is also as a catalyst of high-severity fire: researchers found that high levels of tree mortality in the southern Sierra Nevada strongly correlated with high-severity fire in the 2020 Creek Fire.

The size and severity of recent Sierra-Cascade megafires also caused:

The dry start to the 2020s was followed by one of the wettest winters on record. The 2022-2023 winter dropped as much as 700 inches of snow, setting records in the central and southern Sierra Nevada, causing prolonged power outages and road closures, and catalyzing a new term: “hydroclimate whiplash.”

Although it is not possible to tie any single weather event to climate change, models show that climate change is exacerbating California’s already highly variable climate, making both dry and wet periods more extreme. Warmer temperatures increase the likelihood of rainfall-driven floods and tinder-dry summer conditions that set the stage for extreme wildfires.

Sierra-Cascade Communities Grapple with a new Normal

Naturally, these events carry consequences for the people who live and work in the Sierra-Cascade, reflecting the interdependencies of the natural and human communities of the region. Despite covering one quarter of the state’s land mass, the region is home to around 880,000 people, just over two percent of California’s population. Most residents rely on healthy forests and watersheds for their security, livelihoods, and recreation. Although socioeconomic data specific to Sierra-Cascade communities is limited, residents struggle with issues shared by other rural Californians, including housing costs disproportionate to local incomes, limited access to healthcare services, rural school closures, and limited broadband internet.

Vulnerable residents—including people with disabilities or chronic illness, unhoused people, Indigenous people and people of color, people with limited English proficiency, households without a car, housing- and energy-burdened households, people living in poverty, and the elderly and children—face disproportionate impacts from these circumstances. Many communities suffer from interacting stressors exacerbated by climate change, like extreme heat, excessive wildfire smoke, record-setting snowfall, and destructive landslides. These are just some examples of climate-related trends that regularly threaten communities in the region.

The COVID-19 pandemic further compounded ecological and socioeconomic stressors. Early in the pandemic, lockdowns grounded recreation-driven economies to a standstill. Then, as urbanites sought outdoor space and clean air as a respite from pandemic confinement, demand for recreation surged, raising questions about how to manage use while mitigating negative impacts.

In both 2020 and 2021, visitation was interrupted, and businesses suffered their own form of whiplash during public safety power shutoffs, suffocating wildfire smoke, and the unprecedented closure of national forests across the region (and state) due to extreme wildfire conditions. Meanwhile, some communities struggled to navigate an influx of higher-earning remote workers who contributed to a national trend of spiking housing costs.

A Time of Reckoning

The Sierra-Cascade region is facing tree mortality events and megafires more intense than anything in its recorded history. The threats from wildfire and climate driven stressors facing the area are accelerating at a scale, severity, and pace unimaginable even five years ago. We find ourselves at an inflection point in the most transformative period for the Sierra-Cascade since European settlement in the 1800s and the attempted genocide of California’s Indigenous population.

Looking to the Future

We are part of an unprecedented level of coordination between local, state, and federal agencies, tribal entities, private landowners and organizations, and non-governmental organizations, all working towards a better future for our region.

It is important to note that events of recent years are not uniformly negative. Policy makers and funders met new challenges with unprecedented investments in natural and working lands protection, public lands access, wildfire- and forest-resilience stewardship, and the human capacity to implement these goals. There are also silver linings in recent extreme fire and weather events: despite unprecedented amounts of high-severity fire, many additional acres also burned at low to moderate severity, effectively acting as a “first entry” treatment in overgrown forests.

Scientists, managers, and other stakeholders are coordinating to leverage the benefits from “good fire” to move our forests toward desired, historic conditions. Partners and scientists are working together to plant “forests of the future” in areas that suffered severe fire or high tree mortality and are using new climate-focused strategies to design those reforestation efforts. The 2022-2023 winter pulled the state out of extreme drought for the first time in three years, and land managers seized the opportunity to increase the amount of prescribed fire.

I'm proud of the progress we've made in the Sierra-Cascade over the past 20 years.

Even as the region has experienced profound and tragic change from drought and wildfire, we've made real and meaningful investments in the resilience of our landscapes and the networks of people, organizations, and government agencies that are essential to this critical work. These efforts have helped to reduce harm from recent megafires and both build, and rebuild, the resilience of treasured landscapes and historic communities.

Most importantly, not only has the Sierra-Cascade shown it is ready to advance shared state and local priorities around wildfire and forest resilience, water security, natural and working land conservation, and outdoor access, it is eager for more. We are expanding our work to include new partnerships with California tribes and historically underrepresented communities, finding new ways to work and relate.

If we continue to invest, I'm confident the next 20 years can be a story of regeneration, recovery, and renewal for the Sierra-Cascade and the plethora of wonders it provides California and the world.

Sierra Nevada Conservancy Executive Officer